Build Trust with a Story

The right story builds trust faster than facts can.

Richard Oglesby had a big problem. He needed to create a way for his candidate to connect with the public. Up to this point, the candidate’s public image was of an accomplished, sophisticated lawyer. Impressive if you were being sued but not great for winning votes.

How do you make a successful, eloquent, but not particularly relatable person connect with everyday working-class voters? To make matters worse, it’s May, and the candidate is a long shot.

Oglesby searched for a story to humanize him. A story to show voters the type of person the candidate was. What he needed was a character story. So, Oglesby talked to everyone and uncovered the perfect story from a former coworker.

He heard how, thirty years earlier, the candidate had done hard manual labor—building fences and splitting rails. The former coworker took Oglesby on a ride to see a fence they’d built together.

Oglesby knew he’d struck gold and asked if he could borrow a couple of the fence rails the candidate split years ago.

With rails in hand, he crafted the story of a self-made man: a man who grew up on the frontier. A man who had done railsplitting manual labor to make a living. A man who knew how to work hard just like the voters. He was an ordinary man who grew into a polished, motivating orator.

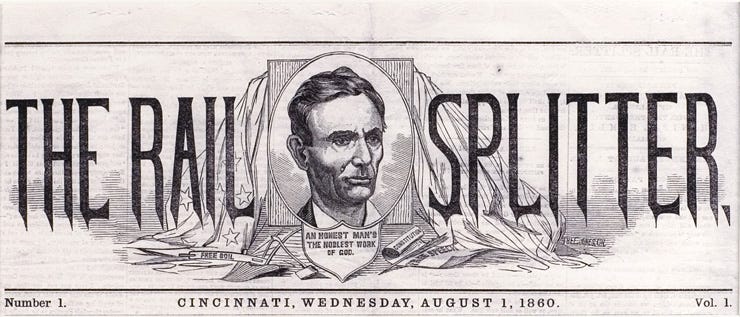

At the state Republican convention, Oglesby had the two rails paraded in before the speech of the dark-horse candidate, the rail-splitter named Abraham Lincoln.

The delegates loved the rail-splitter story, and it became Lincoln’s tagline. It launched him as the presidential pick of the convention. The press wrote this of Lincoln:

“Many delegates in a thoughtful mood, contrasted the present position of the noble, self-taught, self-made statesman. . . with that of the humble pioneer and rail maker of thirty years ago.”

That story and image of Lincoln the rail-splitter painted a sharp contrast with his opponent—an out-of-touch elitist who had likely never split a rail in his life. Lincoln’s story proved so effective that his opponents attempted to rewrite the narrative, trying to label Lincoln a “hair splitter” because of his anti-slavery position. But the more compelling story of the hardworking rail-splitting candidate was what stuck.

The Character Story

Lincoln’s “rail-splitter” story is a great example of how a simple story can build trust by showing character. I call these character stories because they give people a sense of your values and who you really are. And you don’t need someone else to come up with it for you. You can tell your own.

A strong character story shows your values, integrity, and growth. It helps people understand who you are.

These character stories usually fall into three types: passion, professional, or personal.

Passion Story: Share why you do the work you do. This could be about how you got involved in your work and why it matters. Include challenges you’ve overcome, problems you’ve solved, or hard-earned insights.

Professional Story: Highlight your qualifications, experience, and ability to get things done. This could include a story about how you made things happen in your career.

Personal Story: Showcase your grit by including lessons learned, personal challenges you’ve overcome, or failures that shaped your character or leadership approach.

The key to an effective character story is transformation. It shows how a challenge or experience changed your perspective or helped you grow. And it invites the listener to decide what kind of person you are.

When I talk about persuasion, I often start with this personal character story:

“When I was 17, I was too young to legally own a credit card, but oddly, was old enough to sell them.

It was my first sales job, and I loved it. I liked the sales—way more than sitting in college classes. For the first time as a professional, I was finding success. And I could get great with practice.

Selling was fascinating. The training, the persuasion techniques, the little tricks that convert. If the computer lagged, I’d buy time by asking about the weather in Albuquerque or wherever the customer was from. Then I’d pivot to how cold it was where I lived in Maine, and talk about walking through snow to get to class.

One night, the sales supervisor told us to push balance transfers and cash advances. The script was:

“These 0% interest rates won’t last forever!”.

There’s one call from that night I’ll never forget. This nice woman in her 70s with no credit card debt. We hit it off, and I used our script:

“Maybe you need some extra cash for a grandchildren’s graduation or something coming up this summer?”

Deep down, I knew she didn’t need the cash advance. But I followed the script and overcame every objection:

“This offer only lasts until the end of the month. I’d hate for you to miss out.”

Ultimately, I convinced her to transfer $10,000 from her credit card to her checking account.

“We can transfer that money right now and give you peace of mind.”

It was a cash advance she didn’t need.

I ended the call pumped. I posted the sale on the board. I made my $10 commission.

But on break that night, I stood at the coin-op coffee machine and thought: “What the hell did you just do?”

She had trusted me. And I sold her something she didn’t need.

The next day, I quit. Twenty-three years later, I still feel bad about that call and wish I could apologize.

But that one call shaped how I think about persuasion. Persuasion works. That’s what makes it powerful and dangerous. I never wanted to feel that way again, like I had just tricked someone who trusted me.

Build Your Character Story

Start by brainstorming potential stories. Think about moments you're proud of, challenges you've overcome, or failures that shaped your character. Look for the “rail-splitting” experiences that reveal who you are.

The key to crafting a story is to make it short and impactful:

Keep stories concise (1 to 2 minutes or 200-400 words)

Jump right into the action with minimal setup

Follow a clear beginning, middle, and end structure

Conclude with the insight or lesson learned from the experience

Practice the stories to make them feel authentic and natural to share

Be honest and genuine in your storytelling. People can tell when a story feels stretched or manufactured. Test your stories with friends or family to get feedback and refine your delivery.

For example, if I had to tell a character story about Richard Oglesby, I’d start brainstorming:

Three terms as governor

Civil War general

Anti-slavery campaigner

Personal friend of Lincoln

There’s a lot of interesting content, but I’d focus on something different.

I would instead tell you the story of Ogelsby when he was just eight years old. Both parents had died, and the Kentucky farm where Richard grew up was being sold off . So was a man named Tim. Eight-year-old Richard tried everything as a little kid could do to buy Tim’s freedom. He failed. But he promised Tim he would find a way to set him free. It took nearly two decades to fulfill that promise. But after risking it all in the California gold rush, Ogelsby sent money to Kentucky to find Tim and purchase his freedom.

In just 98 words, you learn more about Richard Ogelsby than any professional achievements. That’s a character story.

Think about your own life. Identify the moments that have shaped your character and leadership. Then, craft a compelling story that resonates. By developing a powerful and honest character story, you will make a deeper connection and show how you are the right person to work with.

Source: Richard J. Oglesby, Lincoln's Rail-Splitter, Mark A. Plummer. Illinois Historical Journal, Vol. 80, No. 1 (Spring, 1987), pp. 2-12