The 4-Minute Persuasive Speech

Use four sticky notes to make a persuasive speech

How would you persuade one million people to change their minds? What if it was 1917—before radio, television, or the internet?

George Creel faced this exact problem at the start of World War I. The American government had joined the war and mobilized troops, but the public wasn’t on board with fighting “Europe’s War.”

The president tasked Creel with boosting public opinion for the war. But how? Back then, getting a message to the public was hard. The only medium of mass communication was newspapers, which were already saturated with daily stories about the war.

As Creel considered his options, Donald Ryerson, a Chicago businessman, interrupted to pitch a solution.

What are Americans already doing that we could use to share our message?

At the time, millions of Americans went to the movies every week. Halfway through each movie, the show stopped for 4 minutes so workers could switch the film reels. Ryerson believed those 4 minutes were the perfect time to deliver a message to a captive audience.

Ryerson proposed creating what he called 4 Minute Men—a grassroots network of thousands of people from local towns to go and give speeches during these brief intermissions. The speakers would focus on a single issue and call the audience to a single action.1

Creel loved the idea so much that he put Ryerson in charge. Ryerson got to work, and his team recruited and trained over 75,000 local speakers and wrote hundreds of persuasive speeches for them.2 Throughout the war, the 4 Minute Men gave almost one million speeches. They persuaded people to support the war in big and small ways with calls to action, such as “Donate your binoculars for Navy sailors,” “Buy Liberty Bonds to fund the war,” and “Know how to spot ‘German propaganda.’”3

The 4 Minute Men program worked because it stuck to a persuasive formula. Grab your audience’s attention. Have a single point. Be quick (less than 4 minutes). Always have an action for the audience to take.

While these grassroots speaking tactics later evolved alongside the rise of the radio and television, their persuasive speech principles still work.

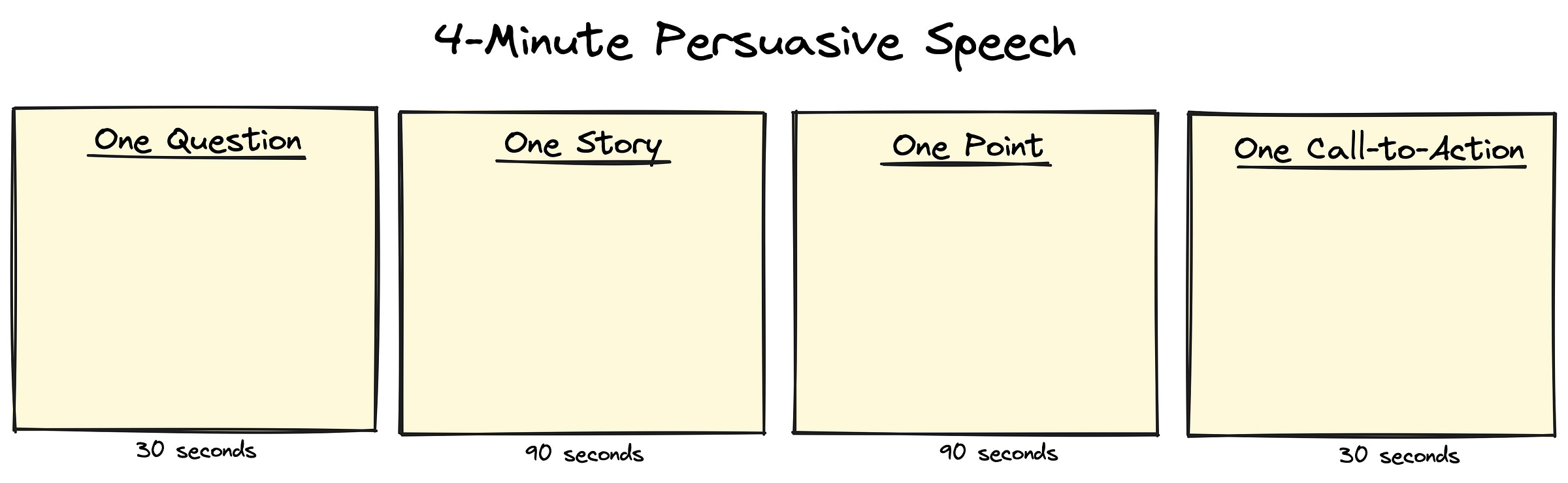

When creating a short, persuasive speech, use the 4-Minute Formula:

One Question

One Story

One Point

One Call to Action

First, ask yourself, “What’s the one point I want my audience to remember?” Brainstorm and write down your answer. The one point is the path of your speech. Everything else your speech includes—the question, story, and call to action—should trace back to your one point.

Once you’ve decided on your one point, it’s time to outline your speech. Grab four sticky notes and write bullet points for each section.

Start your speech with one question framed around your one point. You want to pique your audience’s curiosity so they’ll listen to learn the answer.

Next, tell them one story that answers the question. The more memorable, the better.

After your story, explicitly state the one point you want them to remember. Ideally, say it in a compelling and sticky way.

Close with one call to action for your audience—the one thing you want them to do or think about because of your speech.

For example, if this article were a 4-minute speech, it would look like this:

Try this 4-Minute Formula on your next speech. Grab some sticky notes and create a quick outline. Then practice, and you’ll be ready to give your short, persuasive speech.

Hamilton, John Maxwell. Manipulating the Masses (p. 150-189). LSU Press. Kindle Edition.

Ryerson setup and started the 4 Minute Man program until he was drafted into the War. William M. Blair took over the program and is credited with the successful scaling of the program.

“History Matters.” Four Minute Men: Volunteer Speeches During World War I, historymatters.gmu.edu/d/4970/. Accessed 10 Sept. 2023.

So simple it’s powerful! Thank you Trevor!

This is really good, Trevor